How to teach architectural design in the (new) age of contingency?

It is highly unlikely that today's students will still be able to see virgin steel and concrete as the go-to construction materials by the time they establish their own practices.

Societal concerns about environmental impact will necessarily imply using high-impact, energy heavy resources more sparsely or for very long useful lives. The relationship between architects and materials will become more complex as the profession is increasingly asked for accountability on its tremendous environmental footprint. Materials that are ubiquitous today will need to be substituted by other types of materials: think of biobased materials such as lumber or local mineral materials such as clay. And let us not forget the heterogenous category that is of particular interest to our firm: materials and components from earlier constructions, harvested and prepared for reuse in new projects.

The reuse of building materials leads to immediate and sizeable savings in environmental impact. Sooner rather than later either legislators and/or rising costs will force the building industry to rethink its material sourcing.

Such a radically different use of materials will profoundly change the architectural profession in the coming decades, just like the emergence of reinforced concrete reshaped the building sector and its protagonists in the 20th C. This constitutes an important challenge for those in charge with educating future professionals. As the old world of cheap oil and coal is dying, the new circular world struggles to be born. What professional perspectives can we give to students today? Will our societies tear down and build as much as we do today? Will the design tools we use today still be relevant? What impact will come from the skyrocketing prices of certain materials? Being honest about those uncertainties is a prerequisite for becoming a trustworthy teacher. But what then is there to teach?

Student Samuel Little (Dip.18, AA School, London, 2018/19) has created an imaginable scenario: A trader of surplus steel sets up another company that converts salvaged steel parts into prefabricated portal frames. A partner company followed his suggestion and invested in the idea.

First we need to do away with the dichotomy between two stereotypical teaching methods. A first approach sees architectural education strictly as professional training. In guiding the student’s work, the instructor simulates the contingencies of architectural design: i.e. the constraints imposed by a wide range of parties the student is likely to negotiate with in his/her later professional life, in order to provide a ‘realistic’ experience to the student. An obvious critique on such an approach is that this imprisons the profession. Architects are at the mercy of their commissioners, legislation and the market economy during their entire career. If not during their studies, when will they have the breathing space to come up with alternative ideas? And moreover, it is to be questioned whether the teacher can successfully simulate lifelike, ‘realistic’ contingencies.

On the other side, there is the idea that architectural training should offer unlimited freedom and push the student to the unexplored limits of his/her imagination. ‘Design a house on Mars’, ‘suspend a neighbourhood on helium balloons’, ‘design a building inspired by broccoli’ etc. While such absolute – artistic – licence would certainly be therapeutic for architects with a few years of professional experience, it is often not beneficial for students. Uncertain about exactly what they have been given freedom from, many students turn to the ‘oeuvre’ of the design studio instructor in a desperate attempt to find some form of constraint that can inspire their work.

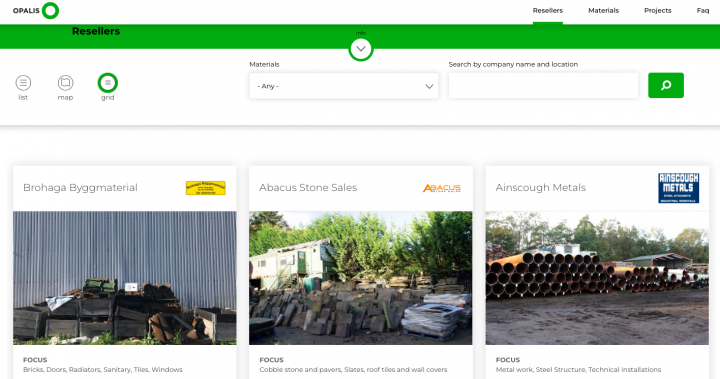

Beyond Opalis is a student-run directory of professional dealers in second-hand building materials. The project was initiated in 2018 when Rotor was teaching the Studio 18 diploma course at the AA School of Architecture in London. Since then, the directory has been maintained and expanded internationally. Soon, it will be integrated in the main website under the name "Opalis Sandbox".

How do you overcome the impossible choice between those two extremes? An extra ingredient is needed in the discussion: the crucial idea that, not only physically, but also mentally we live in constructs of our own making: institutions, legislation, disciplinary frameworks and even our economy and political organigrams are entirely artificial. Hence these can be challenged and even changed. Our students' choice is then no longer limited to either accepting the constraints of the architectural profession or hiding from them in the safety of formal explorations. They are invited to invest a wider realm with their talent to redesign things, and to come up with a plausible proposal on how existing institutions can be reimagined, and what the role of the architectural profession should be in the new age of contingency.

Student Amaya Hernandez (Dip.18, AA School London, 2021) discovered large quantities of reusable materials while investigating buildings for demolition in central London. She organised their reuse and put a demolition company and a trader in touch with each other. Photo: Salvage of York stone pavement

Addressing the reuse of building materials provides a good alibi for such systemic thinking. The absence of a market in perfectly predictable grades of materials forces the students to address the question of materials much earlier in the design process. The current economic conditions that favour cheap new materials over expensive labour need to be reimagined. Building prescriptions and esthetical preferences need to be weighted on their merits. And throughout these processes, the relationship between design and execution takes on new forms, while new and surprising alliances between architects and other practitioners see the light.

That some of the student's proposals reach a receptive audience beyond the school shows that there is a willingness in the building industry to embrace new ideas – and also a dire need for spaces where they can come up.

The Master's Design Studio "Challenges to Metabolic Design" at the University of Ghent (2021) sought solutions to challenges of circular building, such as logistics issues. Gentiel Acar, Jesse Ghyssaert, Ferre Lust and Karen Steukers designed a multifunctional centre for the production, processing and sale of reclaimed materials.They designed the building from existing steel portal frames.

Article by

Lionel Devlieger and Maarten Gielen

Originally published in

Bauwelt n°233 (2022) p. 64-65, as "Wie kann man Architektur im (neuen) Zeitalter der Unwägbarkeiten lehren? Wiederverwertungsstrategien im studentischen Entwurf"