Corked @ Trienal de Arquitectura de Lisboa

Architects and the construction industry are beginning to embrace cork as a natural insulation material. It has exceptional thermal performance and longevity, with often lower attendant emissions (dependent on many factors like transportation) than plastic-based insulation, and without the future waste impact. And cork is impermeable, fire-retardant, rodent-resistant and non-allergenic to boot. Already, cork is preferable, in sustainability terms, to artificial forms of insulation. In our wildest dreams, the cork industry might scale up to provide insulation for northern Europe’s draughty housing stock, reducing energy use now and plastic waste down the line.

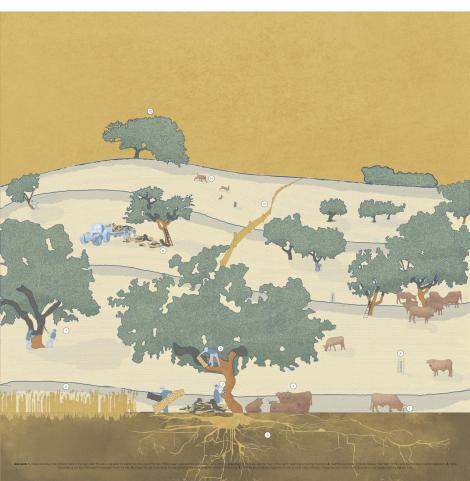

But cork oaks grow almost exclusively in the Mediterranean basin, and only under very limited ecological conditions. Portugal is the world’s biggest exporter of cork with 62 percent of the global total, generating $1.2 billion revenue in 2020. The Portuguese montado ecosystem comprises agroforests that have been an inherent part of the landscape and culture for centuries, and where cork oaks are cultivated alongside crops and roaming cattle, all contributing their nutrients to the soil. It takes at least 25 years—sometimes up to 40 years—for a cork oak to mature, ready for its first harvest. After that, cork can only be extracted—by law—every nine years, by de-barking.

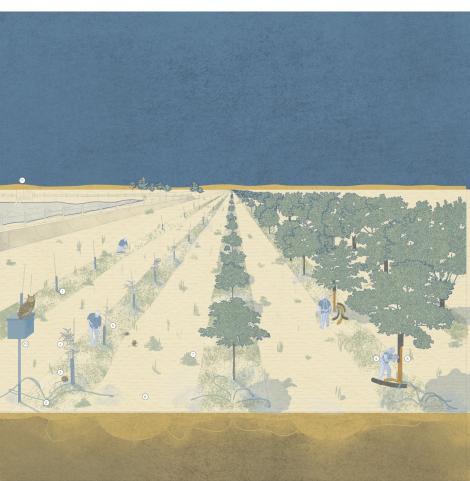

Currently, production is plateauing or falling, due to multiple factors: long lead times before investments in plantations can pay off; climate change and the droughts and fires it brings, both straining cork cultivation and neighboring land use; eucalyptus plantations being selected for rather than new cork plantations; agricultural expansion; even encroachment from a solar farm in one case. Simultaneously, demand is increasing as the potential of cork is realised by new industries. So, the pressure is on to speed up the whole cycle. Cork manufacturers are experimenting with new plantations where trees mature quickly, with the first de-barking projected after only 8–10 years. Such monocrop plantations lack the biodiversity and human traditions of the montado system and require consistent irrigation until the trees reach maturity.

This conundrum reminds us that transitioning to a sustainable building industry is rarely a product-based solution, but requires a shift in our attitudes towards resources. The one universal is that conscientious consumption starts with making the most of our existing building stock by facilitating the reuse of material already sourced and produced, whether organic or not. Rather than shortening the cycle of production—in this case for cork—extending the life cycle of use should be prioritised. At the same time, the question of the availability of land for cork plantations (especially compared with eucalyptus) should be faced head on and addressed through policy.

The good news is that cork is highly durable, making it eminently reusable. But because of the intrinsic ecological constraints and care required for cork production, it should always be considered a precious resource and treated as such, with frugal use and insistent re-use. Other species, human cultures, and positive labor conditions should all be co-cultivated alongside cork oaks to ensure the health of the entire ecosystem.

In the summer of 2022, within the context of the Trienal de Arquitectura de Lisboa, a team of Rotor and AA School Diploma Unit 18 team went on a field trip visiting cork oak montados and forests in central and southern Portugal. We interviewed the stakeholders involved in the cultivation and processing of cork to better understand the current issues and urgencies in producing cork, the future of the market, and its ecological and territorial impact.

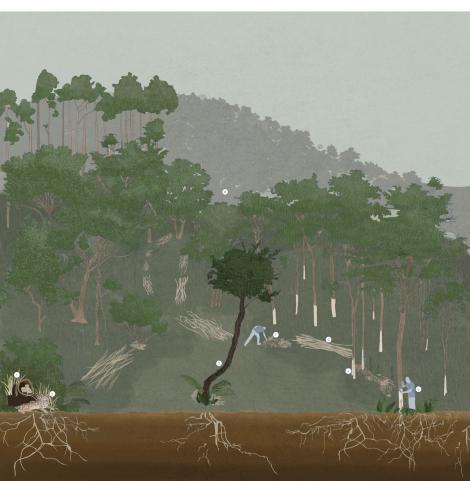

The installation at the Triennale presents the Montado ecosystem, its conservation value and its biodiversity. The focus is to communicate the sophistication and vulnerabilities of this ecosystem as a place of cohabitation for trees, cattle, pastures, humans, and the cork production industry. It resulted in a documentary and a map, some objets-trouvés and one puzzling object in particular: an artificial lynx den.

It encapsulates the dilemma of circularity, sustainability, intensification, and ecosystem care in the land of cork. Fallen trees, their trunks hollowed out over the decades, provide the rare Iberian lynx with an ideal den in which to give birth and raise their kittens. But such natural dens are harder and harder to come by, and with Portugal’s forests facing a multitude of threats, the lynx’s habitat is precarious. So, ten years ago, Liga Para a Protecção da Natureza initiated a programme to fabricate artificial lynx dens and insert them into select forests. The dens are made out of iron framework clad with… cork.

Documentary by

James Westcott with Aude-Line Duliere and Arne Vande Capelle

Editing: Nena Aru, Amaya Hernandez and Ele Mun.

Shot at / interviews with:

Companhia das Lezírias / Rui Alves

Herdade da Lavandinha / António Freitas

Herdade da Venda Nova / Nuno Oliveira

Quinta da Moenda / Samuel Vieira

Tapada Nacional de Mafra / Margarida Gago

Liga para a Protecção da Natureza / Rita Martins, Jorge Palmeirim

Drawings by

Amaya Hernandez, Leander Decloedt

Project with the scientific support of

Liga Para a Protecção da Natureza (Rita Martins, Jorge Palmeirim), Dr. Harriet Allen and Dr. Elisa Dierickx

Thanks to

Pedro Aguilar Vieira (Quinta da Moenda), Rafael Alves da Rocha (Amorim), Leonie Dekoning, Dr. Elisa Dierickx, Cristina Marques (Tapada Nacional de Mafra), Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Ben Ibbotson and Joel Newman (Architectural Association AV), Nathalie Brison and Selda Cinal (WBA), Inês Lourenço, Teresa Quartilho

Produced with the support of

Wallonie-Bruxelles Architectures (WBA)

Wallonie-Bruxelles International – Lisbon (WBI)